Category Archives: Game Design

How to (Speed) Pitch Your Game

While at Gen Con my business partners from Moon Yeti Games and I had a chance to be part of the Publisher Speed Dating event run by James Mathe of Minion Games. I will refrain from making any comments about the games themselves. However, I am writing this article because I was a little shocked at how poorly people were pitching their games.

A while back I wrote an article called How To Teach Games. I’m using a similar model for this article.

The Scenario:

You’ve got 5 minutes to pitch your game. It’s all set up, ready to go. A publisher walks up to your table. What do you do?

The Pitch:

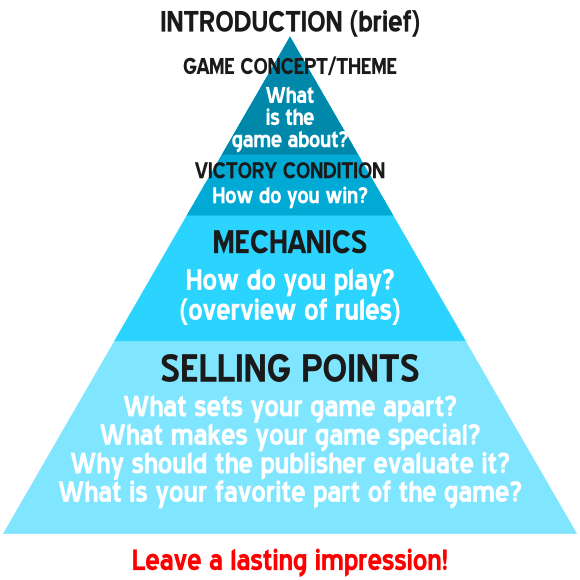

When teaching games I like to work top down and start very vague and get more and more detailed. A pitch doesn’t really work that way. You’ve got to figure out a way to skip over a bunch of the basics of your game and dive deep into the selling points. Here is a graphic I made that should help:

The sizes of the different portions of the pyramid represent the amount of time you should spend on that section. Let’s break it down:

INTRODUCTION:

This should be limited to your name and handshakes. Give a business card and sell sheet. Otherwise don’t waste time here.

GAME CONCEPT/THEME:

Limit this to 10-20 seconds. Basically just give the background of the game concept. There’s no reason to go into a back story of why you are designing it or how it may serve humanity. Be succinct and move on.

MECHANICS:

This part is more important and is where you should spend about 1-1.5 minutes. Publishers will need to know how a game is played. They understand that if a turn in a game requires you to work through 15 different phases, then perhaps the game isn’t as streamlined as it could be. Give a good overview of the rules and how a basic turn works. You don’t need to share every rule of the game nor do you need to share the “exception” rules that are slightly different than the norm. Just share the normal, standard rules for the game. Work through the whole thing and then come back to the selling points…

SELLING POINTS:

Here is where you make or break the deal. This should be the bulk of the pitch. Publishers want to know what makes your game special. There are a lot of games out there. There are a lot of designers out there. There are TONS of unpublished games out there. So what makes yours special?

I refer to it as the “hook.” Tell the publishers what the hook is. The hook refers to the thing that’s different than any other game.

- Are you utilizing components in a new way?

- Are you using a new mechanic?

- Are you modifying an old mechanic in a new way?

- Is your theme so amazing?

Hopefully there is something that sets your game apart. This is where you share that. This is where you emphasize how your game is special. This is where you make your case. Figure out what makes your game great and make sure the publishers understand!

LEAVE A LASTING IMPRESSION:

Hopefully your game will leave a lasting impression. It is wise to allow 20-30 seconds at the end for questions from the publisher. Answer their questions cordially and then thank them for their time.

Aftermath:

Congratulations! You just made the best sales pitch ever! Now what?

Publishers are different. Some may offer a contract on the spot (this is rare). If so, congratulations! Some may ask for a prototype. It’s a good idea to have an extra prototype on hand. Here’s where it gets a little sticky: what if two publishers ask for a prototype? (You should have a publisher priority list – meaning you’d rather work with pub A than pub B. Give the proto to pub A!) Sometimes publishers will love the game but will want to consider it before approaching the designer outside of the sales pitch. Often this is due to publishers needing time to discuss the prototype and the designer with their internal team.

Often the aftermath requires patience. Feel free to contact a publisher, but don’t be pushy. Publishers see a lot of games and often have a lot on their plates. Rest assured, though, knowing that you at least made a good sales pitch!

Have you had a successful sales pitch? Do you have a different method? I’d love to hear about them. Also, let me know if you have any comments about this method. Thanks for reading.

Game Design Philosophy

After killing Brooklyn Bridge I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about who I am as a designer and what I want to design. So I sat down last night and examined the top 50 games on BGG to see what elements they had in common. My goal was to understand which elements are enjoyable to me and to understand how they are incorporated into some of the best games in the world.

What I ended up with was a list of five things that I feel are important to my game designs. Please note that this article discusses the things that I personally feel are important to good game designs. Your opinions will likely vary. I urge you to create a similar list that you can use as a tool to help you make sure your game design is going down a path that is acceptable to you.

I now realize that had I had this list before working on Brooklyn Bridge, it probably would have turned out to be a better game. I may attempt to re-design it now that I have this list to use as a design tool.

My previous design philosophy was simply to make fun games. That’s not a good philosophy because it is extremely difficult to measure or quantify.

What follows are 5 elements or guidelines that I will seek to follow when designing games. For each I will demonstrate how they exist in both the immensely popular Ticket to Ride and the soon-to-be immensely popular Scoville. Using these as a guideline will provide a measurable way to know whether or not what I am designing has the potential to be an enjoyable game.

1: Quick to Teach / Easy to Understand

This DOES NOT mean the game is simple or light.

This DOES mean that it can generally be set up in 5 minutes and taught in about another 5. I don’t want to spend 20 minutes setting up a game and then another 15 trying to teach it to people.

Ticket to Ride Example: TtR (or perhaps T2R to you) can be set up and explained in about 5 minutes total.

Scoville Example: Scoville requires a little more setup than this guideline but it can be taught in 5 minutes for sure.

Other successful games like The Settlers of Catan are relatively simple to set up and teach. Of course there are very successful games that do not quite meet these criteria. There’s nothing wrong with that. Remember, this is MY design philosophy. So the games I will design will likely meet these things.

2: Minimal “Exception” Rules

“Exception” rules are those that require an individual point of emphasis when teaching. The fewer of these types of rules in a game the “Quicker” and “Easier” it is to teach and understand. This guideline ties into the first one. I will not be designing games that have a long list of FAQs or “exception” rules.

Ticket to Ride Example: There are on the order of two exception rules. 1) You can’t draw two locomotives from the face up pile. 2) If there are ever three locomotives in the face up set then you replace all face up cards.

Scoville Example: There are slightly more than than TtR, but they apply during two phases. 1) You can bid zero and ties are broken from previous turn order. 2) Harvesting: No doubling back, No sharing or going through another player.

The idea here is that the rulebook should be streamlined and straight forward. If your game has a bunch of singular exceptions that need to be covered, I recommend putting that information on a player guide for each player. Then when teaching the game you can simply point out that there are some exceptions and that players should reference the guide.

3: Limited Actions or Choices Per Turn

One easy way to add tension in a game is to limit what players can do. Agricola does this with great success. Most Stefan Feld games do this very well. The idea is that while you may not have a lot of different choices to make, there is some tension in trying to choose the optimal choice. Similarly you may have a lot of options but can only choose 1 or 2 per turn.

Limiting the number of actions or the number of choices a player has on their turn also has two notably positive effects:

- Downtime is minimized

- Analysis Paralysis is limited

Downtime decreases if a player only has a few options to choose from. Analysis paralysis, or a player’s inability to make a decision, is limited since there are only so many combinations of things to work through.

Ticket to Ride Example: On your turn you only have three options. 1) Draw train cards. 2) Draw Destination Tickets. 3) Play trains to the board. That’s it. It’s so simple. But the depth of the game comes from decisions like, “Should I draw train cards one more time or should I burn a locomotive card this turn?”

Scoville Example: Each round has four phases, each of which are simple. Bid, Plant, Harvest, Fulfill. Each phase is simple enough that you have a limited number of options. Choices include how much to bid, which pepper to plant, how to harvest, and what to fulfill.

This philosophy guideline was greatly influenced by my recent play of Attika. In Attika you have two choices: Draw tiles or build. That limitation is so stupidly simple and yet the game builds up as it moves along and is quite enjoyable. Which leads me to the next guideline.

4: Include a Natural Buildup

The idea here is that the decisions you are making during a game accelerate and either feel more tense or more important or hopefully both. Games do this differently. Some games build up because you have access to better/more resources. Other games build up because the game presents better scoring opportunities or something of the sort.

When a game builds up naturally it turns it into an emotional experience where you are drawn into the game. When you make a decision early in a game you don’t want a bad choice to destroy your chances. But when you make a decision late in the game you want a good choice to be able to greatly help you out.

Ticket to Ride Example: As the map fills up the decisions become more tense. You might begin to worry that a player will fill up a connection that you needed. Or you might worry that there are not enough turns left to complete all your destination tickets.

Scoville Example: As the fields are planted each round there are more/different cross-breeding opportunities. Your decision space opens up. As you get better peppers there is the sometimes tense choice of whether to plant it for the bonus points or save it and fulfill a recipe to prevent someone else from getting it.

Brooklyn Bridge had no build up at all. I think that good games should include some sort of build up or acceleration. If it fits naturally into the game, that’s even better. What I desire from fun games is that as the game builds up and things get more tense and exciting, that I am getting some sort of increased emotions from my gaming experience. Without a build up I feel like my game designs would lack that emotional aspect.

5: Players Should Be Rewarded

Continuing with the “emotion” idea, I feel it is important that players be able to be rewarded for the actions they take during the game. Point salad games, like several Feld games, do this on just about every turn. When every choice you make gives you points there is a natural positive emotion attached to that. On the other hand if the choices you make never reward you then you’ll likely not have a natural positive emotion during the game. There is something to the idea of moving your scoring marker around the board and seeing yourself jump past other players.

Ticket to Ride Example: A positive emotion and rewarding moment in TtR comes each time you complete a route. This is a secret positive emotion but it is present and it feels awesome.

Scoville Example: When players plant a better pepper and earn an award plaque from the Town Mayor there is a positive emotion and rewarding moment. They know that their action just earned them points that no other player will be able to match.

These types of rewards that provoke positive emotions will likely result in players enjoying the game more than an equivalent game that is void of rewards. I want to design games that will provoke positive emotions and one way to do that is by rewarding players.

I wish I had written this article a long time ago. Having these guidelines in place will allow me to check off whether or not my current designs are meeting the criteria. That should be easy enough to recognize. If they don’t meet the criteria I’ll be able to tell and hopefully it will allow me to come up with design tweaks that turn my designs into awesome games.

What’s your design philosophy? I’d love to hear how yours differs from mine. Feel free to share in the comments. Thanks for reading!

When to Fold ’em – Quitting on your Designs

I am calling it quits for now with the Brooklyn Bridge game design. This is the inspiration for this article.

So this begs the question: When do you quit on a game design?

You might think that would be as easy as asking if the game is any fun. But it’s not that simple. You see, there is this thing called “passion.” A lot of game designers utilize it when create their designs. I know I do. But let’s step back even further and discuss a designer’s philosophy.

Why do I design games?

This is an important question designers should ask themselves. Answers could be all over the map:

- You want to earn bazillions of dollars

- You like games

- You want to win the Spiel des Jahres

- You’re creative

- You want people to like you because of your design

- You’ve got some great game ideas

- It’s what you love to do

Whatever the reason, it’s important that you understand the answer to the question of why you design games.

Once you’ve got that figured out, the answer to the first question, when to quit on a game design, can be more easily answered. Often it is important to remove the emotional side of game design before you can truly quit on a design. People put a lot of effort and time and money into their game designs. So to just quit on a design is like throwing all of that effort, time, and money out of the window. Sure, there are usually some takeaways from that design, but ultimately it’s a big loss.

Here is the reason I design games: it’s a fun hobby.

Therefore, if designing a game stops being fun, I dump it.

Why did I Quit on Brooklyn Bridge?

I was originally inspired to design a Brooklyn Bridge game when I was watching a BBC documentary about its construction. The discussion about the caissons was fascinating and I immediately had thoughts about a risk vs. reward mechanic built around how long workers would stay in the caisson. Sweet!

So I made a time based worker placement game about the Brooklyn Bridge. Workers could get sent to work in several different locations (Caissons, Brickyard, Cableyard, Training Office). Each turn the workers would advance some distance in those locations. The longer they advanced, the better the rewards when they would be removed. This is not dissimilar to riding the gears in Tzolk’in. But there was a big change… other players could help you advance even faster if you placed your workers correctly. That’s awesome!

That sounds great. But it didn’t work. That’s not to say it couldn’t work. I’m definitely keeping the mechanic for another design. It just didn’t all work for this design.

The game took too long. It felt same-y (meaning there wasn’t enough variability/replayability). And ultimately the decisions you made throughout the game didn’t get more tense or more interesting. That’s not good.

I got through about 15 playtests and after the final one I realized I just wasn’t enjoying working on this design. It was at that point that I detached emotionally from the game and felt at peace to let it go. I quit on the design.

I believe it has potential. I believe that are good elements in there. If a publisher wants it and is willing to develop it I would happily work with them. But I quit because I was no longer enjoying it.

Why do You Quit on your Game Designs?

I urge you to go back to my question of “Why Do You Design Games?”. Knowing the answer to that can greatly help you know when to quit on a design.

Most designs won’t succeed. As a designer it’s important to know when to give up on one and start on the next. If you spend too long on a design that doesn’t have a future or that isn’t enjoyable or that is unpublishable then maybe you should consider breaking up with the game. I’ve met a whole bunch of designers with tons of games that never made it. Some have been working on the same games for years. Others have thrown away games that are only a few days old. There is a level of recognition where they realized the game wasn’t worth it.

The sooner you can realize that a game isn’t deserving of your time, the sooner you can design one that is!

Coarse vs. Fine: Editing your Game

When Michaelangelo started carving David he didn’t grab his tiniest chisel and smallest hammer. He grabbed his big chisel and big hammer (I assume). Why? Because he needed to coarse cut the stone away to roughly the right size. Then once the bulk of the stone was removed he could use his fine tools to chip away slowly.

This Coarse Vs. Fine concept is the core of this quick article on game design.

When designing a game it is often easy to think of a lot of awesome things that could be in the game. I know there are people who put in everything but the kitchen sink into their game designs and then remove things as we go. This coarse/fine idea fits well with that design concept. There are others who start with a simple mechanic or a theme and then add things only when needed. This article doesn’t address that situation. I’ll cover that design realm another time. But for those of you who start big and remove the unnecessary components, keep reading!

The Stone

You must choose wisely… Not really.

When you start a game design you’ll choose a mechanic or a theme or both. This is like going to the quarry and picking out the stone you’ll start with for the sculpture. When picking the stone you want to make sure it is big enough, has the right grain structure, possesses the desirable color and so on. Similarly, when choosing the mechanic and theme you’ll want to make sure you’ve got a lot of different components that fit with the theme and mechanic.

So go ahead and make your choice. Once you’ve got your stone it’s…

Hammer Time!

This is where you design the game, prototype it, and play it.

Once you’ve played it there will likely be parts of the game that don’t work, are broken, don’t make any sense, or aren’t fun. Take the hammer to them!

Like making a sculpture, once the stone is in your workshop you typically sketch a little on the block and then start taking the hammer to it. It is time to take away big chunks of the stone that you know you won’t need. Don’t be afraid to remove those big chunks of stone.

Back in the game design world, this is where you remove those chunks of the game that were broken, didn’t make sense, or weren’t fun. Don’t be afraid to get rid of them.

If you have things that don’t make sense thematically… Hammer Time!

If you have mechanics that don’t work right… Hammer Time!

If mechanic X isn’t any fun… Hammer Time!

If you aren’t happy with something… Hammer Time!

The point here is to narrow the focus of the design. Take away the things that obviously don’t belong. If something is iffy, save it for later. Playtest it over and over until you feel you’ve removed all the big chunks. Then put away the hammer and grab the chisel.

Chisel Time!

I know that “Chisel Time” doesn’t sound as awesome as “Hammer Time” but it’s much more important in terms of game design and development. It’s easy to break away the big chunks of a game. But using your fine tools to craft something with elegance and class is very difficult.

Chisel Time is really where you move from game design into the game development realm.

Once you have finished with the hammer you are left with a block of mechanics, components, and concepts that closely resemble a final product. The nitty gritty down and dirty work happens in the Chisel Time phase. This is where you playtest, tweak, playtest, tweak, playtest, tweak, and on and on. You’re no longer removing large chunks from the design. Rather you are polishing the remaining elements to make them as streamlined and perfect as they can be.

So What?

The whole idea here is to give a perspective about how game design works. Relating game design to sculpting stone allows me to have the right mindset when I’m working on a game design. Early in the process it is important to put the elements together and make a prototype. You can’t take a hammer to it unless you know what you want to remove.

Once you’ve hammered away the big chunks then your mindset changes. You’ve got the mechanics you want. Now it is important to figure out how to balance the mechanics and the currency and the other elements in the game. You go from removing elements to refining elements. That’s a lot of work, but it is also one of the most rewarding parts of the design process. Just a couple weeks ago I had refined an element for Brooklyn Bridge and one of the players mentioned how it took it from “Good” to “Special.” That’s really what you’re looking for during Chisel Time.

How do you design games? Do you start big and remove things as you go? Or are you the opposite where you start with a simple element (mechanic or component) and then add the things that are needed?