Blog Archives

Is Impossible Impossible?

Impossible is a new game design I have been working on. It is a race game where players are racing to recognize and build hex-based designs of impossible geometry reminiscent of the work of M.C. Escher.

You can learn of the design in my previous article: Hex-tile Prototype: Impossible.

Basically players will be grabbing hex-tiles from the pile and trying to create the 2D representation of the impossible shape. The first player to complete the image places their meeple on the highest scoring spot. The next player to finish claims the next spot. And so on.

Basically players will be grabbing hex-tiles from the pile and trying to create the 2D representation of the impossible shape. The first player to complete the image places their meeple on the highest scoring spot. The next player to finish claims the next spot. And so on.

The game continues over a pre-determined number of rounds. Each round has a different impossible shape. After all rounds are completed the total points are added to decide the winner.

Mechanically this game works. It is mechanically simple, easy to learn and understand, can be set up and taught in 3 minutes. These are all great things for a game design.

So What’s Wrong?

I am a very visual person. I can recognize visual patterns. I can visualize 2D and 3D geometry quite well.

I’m beginning to feel as though I’m the only one in the world who can play this game.

In the past two weeks I’ve solo tested this and playtested it with three other people. Small sample group for sure. But those people are very intelligent people. I’ll test this further, but my inclination is that this game may just be impossible for some percentage of people to play.

Spatial Ability

According to a paper titled, Visual Spatial Skills (2003) , out of Penn State University, spatial ability is defined thusly:

Spatial ability is the over-arching concept that generally refers to skill in representing, transforming, generating, and recalling symbolic, nonlinguistic information. Spatial ability consists of mental rotation, spatial perception, and spatial visualization.

In the case of Impossible this is most definitely relevant. So what percentage of the population has spatial ability in their skill set?

This is from the Wikipedia page on Visual Thinking:

Research by child development theorist Linda Kreger Silverman suggests that less than 30% of the population strongly uses visual/spatial thinking, another 45% uses both visual/spatial thinking and thinking in the form of words, and 25% thinks exclusively in words. According to Kreger Silverman, of the 30% of the general population who use visual/spatial thinking, only a small percentage would use this style over and above all other forms of thinking, and can be said to be ‘true’ “picture thinkers”.

I’m starting to believe that I’m one of these so-called “picture thinkers.”

So it seems that 30% of the population strongly uses visual/spatial thinking. And a small subset of those use visual/spatial over all other forms.

Is visual/spatial required to be able to play Impossible?

My answer is, “yes.”

Marketability of Impossible

As a game designer I want to make games that are accessible to a large audience. The larger the anticipated audience is, the more likely the game is to signed by a publisher, and subsequently the more likely it is to succeed.

With 70% of the population not considered to be visual/spatial thinkers, that eliminates a huge percent of the potential audience for a game. I don’t think a publisher would be interested in a game that cannot be played by 70% of the population.

So at this point Impossible will earn a spot in my drawer of shame, where all my designs go to die when I decide to stop working on them.

I believe Impossible is a fun, quick, and interesting game that utilizes 3D geometry in 2D space. I think the artwork could make it look visually stunning. I believe it would fit at a good price point for a general audience.

Perhaps the best avenue for Impossible would be as an app for your phone or tablet. This would be quite easy to implement and then could be targeted specifically to people who would find it enjoyable. Who knows what the future holds for Impossible.

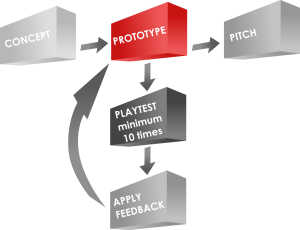

Game Design: Starter Prototyping Tools

I recently asked myself the following question: “If I were to start over with game design, which prototyping tools would I buy to get started?” I’ve made numerous prototypes and I’ve learned what to do and what not to do. So today I present a set of prototyping tools to help get you started as a game designer.

When I got started out I didn’t want to throw a lot of money at prototypes. This was because I had no idea if the prototypes would ever actually go anywhere. I was fortunate to have a wife who used to do physical scrapbooking. So I had some tools available to me that wouldn’t have otherwise been available.

Never-the-less, there are some key tools and resources that I think every game designer can utilize to make high quality prototypes at low(ish) cost and with relative ease. For the sake of this article I will assume that you can print on photo paper (I recommend Kodak 8.5×11 – 100 sheets).

Game Prototyping Resources

First, let’s cover where to get some basic resource type things. These are my go-to retailers for these items:

- CUBES: 1,000 1cm cubes from EAI Education for $16.95

- MEEPLES: Avatar pawns from TheGameCrafter.com for $0.15 each

- DICE: Buy a set of Tenzi dice! (Or search Amazon or eBay)

- CARDS: Blank Cards – Different Sizes – from TheGameCrafter.com

Game Prototyping Tools

Things that are not mentioned above include boards, tiles, tokens, reference sheets, rulebooks, and more. I generally use the same process to make all of those except a rulebook. I don’t typically make a rulebook.

To make my prototype components feel like high quality I purchase the following materials:

- Matte board remnants from Hobby Lobby for super cheap. You can get a stack of about 25 12″x12″ matte boards for about $6.

- Kodak Photo Paper (100 sheets for ~ $15)

- Non-OEM ink for my inkjet printer via eBay. (I bought 5 full sets of ink cartridges for ~$20)

- Glue Sticks – you’ll want to keep several on hand.

I often create artwork and then print it on the photo paper. I glue it down to the matte board. Then I break out my most highly recommended tool: The Rotary Cutter!

The Rotary Cutter

Easily worth the cost!

This has been my most-used tool for creating game prototypes.

I have a Fiskars rotary cutter similar to the one shown in the picture. You can buy it here:

It isn’t the best cutter. You can pay a lot more money for better cutters. But it does exactly what I need it to do for my prototypes. Other cutter options include:

There are more options than those, so if you don’t like those options feel free to do more thorough searching.

I use this tool to cut out the components that have been printed and glued to the matter board. This cutter works well enough for that.

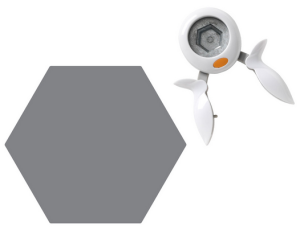

Punches

Great for cardstock chits!

Other great tools for designers are punches. These are used to quickly create tokens and chits. When I create tokens and chits I usually prefer printing the artwork onto thicker stock paper so they are more rigid. 90lb or 100lb paper is usually a good weight.

There are a plethora of different punches out there, but for the sake of board games you’ll most likely be interested in circle and hex punches and corner rounders. Here are some options.

- Fiskars Squeeze Punches

- Fiskars Lever Punches

- Fiskars Corner Rounders

- List of Punches on Scrapbook.com

As before, go ahead and do some more searching to find the right product for you.

Sharpies

I am firmly in the Sharpie camp. I love them. They are bold, colorful, and extremely useful. Sharpies can be used to create prototype components rapidly, especially in the case where you own blank cards because you took my recommendation above.

By having a variety of Sharpies you become an unstoppable force of game design awesomeness!

I use them to create prototypes. I use them to mark up my prototypes. I use them to revise my prototypes. I use them to draw silly pictures for my kids.

Seriously, Sharpies are fantastic. I feel they are a must-have for any game designer, if for no other reason than to be able to practice your signature for the time when lovers of your games will ask for your autograph for their game box!

I feel like this article needs more tools in it, but those are the only tools I utilize on a regular basis. Are there prototyping tools that you use regularly? Post a comment and let everyone know which prototyping tools you prefer!

Grand Illusion Update

Today I wanted to report on the progress of The Grand Illusion. Normally I do that on Thursdays and I was planning on posting a game review today but I’m excited about the game so I figured I’d write about it.

What’s New?

I’ve begun prototyping! I have created a deck of skill cards. These cards represent the 9 types of magic in the game. The types of magic are in two separate tiers: basic and advanced. There are 6 basic types and 3 advanced types. Here is a picture showing the skill cards (thanks to The Game Crafter for blank cards – They have blank poker cards on sale right now for 1 cent each!).

Collect these and use them to perform never-before-seen magic tricks to appease your growing audience!

Those are hand-drawn icons, people!

What’s Next?

The next step for the prototype is to create a deck of Trick cards. These are cards that represent magic tricks. During the game you’ll need to collect the skill cards shown above and then turn them in to complete the magic tricks.

Once you perform a magic trick you will earn the rewards and audience shown on the card.

So let’s discuss audience… Audience is actually a currency in the game. It is necessary to build an audience during the game or you will not meet the requirements on your Grand Illusion card. So each time you perform a trick, if successful, you will gain audience. In the game you will collect skill cards, spend them to perform tricks, gain audience and increase your skills to be able to perform better tricks.

There will definitely be some engine building in the game. The goal of this design is to be an entry-level game with an easy rule set that is quick to teach and play. The main mechanics are set collection and engine building.

Engine Building

Engine building in games refers to the idea of obtaining some ability or benefit that let’s you do things a little better, then getting another one that builds on the previous ability or benefit.

In The Grand Illusion the engine is represented by the skills each magician will gain. Will you become a master of vanishing acts? Perhaps you’ll be the best at restoration magic? Ultimately you’ll have to get proficient at at least two basic types of magic and one advanced magic.

The question I’m currently struggling with is how exactly to create the engine building element. I have two options I’m considering:

1) Splendor-Like

In the game Splendor players turn in poker chips to grab a card from the table. Once they grab that card it usually acts as a poker chip. So for future card grabs they need one less poker chip. This would work perfectly for The Grand Illusion but I don’t want to copycat an existing game.

2) Tech Tree

A tech tree is something where you must complete “Level 1” stuff before you can work on “Level 2.” So in The Grand Illusion I could have a tech tree (pyramid) of trick cards on the table. When a player would perform a trick they would place a token of their player color on the trick to show they’ve completed it. This would also direct their play as there would be advantages and disadvantages for breadth versus depth.

I think that once I create the Trick deck I’ll try out both of these options. The Splendor-like version may work better, but I’m more drawn to the Tech Tree version since it is more original.

My goal is to prototype the skills deck this weekend and aim for the first playtest next week! Thanks for reading. I’d love to hear your thoughts about the different engine building options.

Game Design Philosophy

After killing Brooklyn Bridge I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about who I am as a designer and what I want to design. So I sat down last night and examined the top 50 games on BGG to see what elements they had in common. My goal was to understand which elements are enjoyable to me and to understand how they are incorporated into some of the best games in the world.

What I ended up with was a list of five things that I feel are important to my game designs. Please note that this article discusses the things that I personally feel are important to good game designs. Your opinions will likely vary. I urge you to create a similar list that you can use as a tool to help you make sure your game design is going down a path that is acceptable to you.

I now realize that had I had this list before working on Brooklyn Bridge, it probably would have turned out to be a better game. I may attempt to re-design it now that I have this list to use as a design tool.

My previous design philosophy was simply to make fun games. That’s not a good philosophy because it is extremely difficult to measure or quantify.

What follows are 5 elements or guidelines that I will seek to follow when designing games. For each I will demonstrate how they exist in both the immensely popular Ticket to Ride and the soon-to-be immensely popular Scoville. Using these as a guideline will provide a measurable way to know whether or not what I am designing has the potential to be an enjoyable game.

1: Quick to Teach / Easy to Understand

This DOES NOT mean the game is simple or light.

This DOES mean that it can generally be set up in 5 minutes and taught in about another 5. I don’t want to spend 20 minutes setting up a game and then another 15 trying to teach it to people.

Ticket to Ride Example: TtR (or perhaps T2R to you) can be set up and explained in about 5 minutes total.

Scoville Example: Scoville requires a little more setup than this guideline but it can be taught in 5 minutes for sure.

Other successful games like The Settlers of Catan are relatively simple to set up and teach. Of course there are very successful games that do not quite meet these criteria. There’s nothing wrong with that. Remember, this is MY design philosophy. So the games I will design will likely meet these things.

2: Minimal “Exception” Rules

“Exception” rules are those that require an individual point of emphasis when teaching. The fewer of these types of rules in a game the “Quicker” and “Easier” it is to teach and understand. This guideline ties into the first one. I will not be designing games that have a long list of FAQs or “exception” rules.

Ticket to Ride Example: There are on the order of two exception rules. 1) You can’t draw two locomotives from the face up pile. 2) If there are ever three locomotives in the face up set then you replace all face up cards.

Scoville Example: There are slightly more than than TtR, but they apply during two phases. 1) You can bid zero and ties are broken from previous turn order. 2) Harvesting: No doubling back, No sharing or going through another player.

The idea here is that the rulebook should be streamlined and straight forward. If your game has a bunch of singular exceptions that need to be covered, I recommend putting that information on a player guide for each player. Then when teaching the game you can simply point out that there are some exceptions and that players should reference the guide.

3: Limited Actions or Choices Per Turn

One easy way to add tension in a game is to limit what players can do. Agricola does this with great success. Most Stefan Feld games do this very well. The idea is that while you may not have a lot of different choices to make, there is some tension in trying to choose the optimal choice. Similarly you may have a lot of options but can only choose 1 or 2 per turn.

Limiting the number of actions or the number of choices a player has on their turn also has two notably positive effects:

- Downtime is minimized

- Analysis Paralysis is limited

Downtime decreases if a player only has a few options to choose from. Analysis paralysis, or a player’s inability to make a decision, is limited since there are only so many combinations of things to work through.

Ticket to Ride Example: On your turn you only have three options. 1) Draw train cards. 2) Draw Destination Tickets. 3) Play trains to the board. That’s it. It’s so simple. But the depth of the game comes from decisions like, “Should I draw train cards one more time or should I burn a locomotive card this turn?”

Scoville Example: Each round has four phases, each of which are simple. Bid, Plant, Harvest, Fulfill. Each phase is simple enough that you have a limited number of options. Choices include how much to bid, which pepper to plant, how to harvest, and what to fulfill.

This philosophy guideline was greatly influenced by my recent play of Attika. In Attika you have two choices: Draw tiles or build. That limitation is so stupidly simple and yet the game builds up as it moves along and is quite enjoyable. Which leads me to the next guideline.

4: Include a Natural Buildup

The idea here is that the decisions you are making during a game accelerate and either feel more tense or more important or hopefully both. Games do this differently. Some games build up because you have access to better/more resources. Other games build up because the game presents better scoring opportunities or something of the sort.

When a game builds up naturally it turns it into an emotional experience where you are drawn into the game. When you make a decision early in a game you don’t want a bad choice to destroy your chances. But when you make a decision late in the game you want a good choice to be able to greatly help you out.

Ticket to Ride Example: As the map fills up the decisions become more tense. You might begin to worry that a player will fill up a connection that you needed. Or you might worry that there are not enough turns left to complete all your destination tickets.

Scoville Example: As the fields are planted each round there are more/different cross-breeding opportunities. Your decision space opens up. As you get better peppers there is the sometimes tense choice of whether to plant it for the bonus points or save it and fulfill a recipe to prevent someone else from getting it.

Brooklyn Bridge had no build up at all. I think that good games should include some sort of build up or acceleration. If it fits naturally into the game, that’s even better. What I desire from fun games is that as the game builds up and things get more tense and exciting, that I am getting some sort of increased emotions from my gaming experience. Without a build up I feel like my game designs would lack that emotional aspect.

5: Players Should Be Rewarded

Continuing with the “emotion” idea, I feel it is important that players be able to be rewarded for the actions they take during the game. Point salad games, like several Feld games, do this on just about every turn. When every choice you make gives you points there is a natural positive emotion attached to that. On the other hand if the choices you make never reward you then you’ll likely not have a natural positive emotion during the game. There is something to the idea of moving your scoring marker around the board and seeing yourself jump past other players.

Ticket to Ride Example: A positive emotion and rewarding moment in TtR comes each time you complete a route. This is a secret positive emotion but it is present and it feels awesome.

Scoville Example: When players plant a better pepper and earn an award plaque from the Town Mayor there is a positive emotion and rewarding moment. They know that their action just earned them points that no other player will be able to match.

These types of rewards that provoke positive emotions will likely result in players enjoying the game more than an equivalent game that is void of rewards. I want to design games that will provoke positive emotions and one way to do that is by rewarding players.

I wish I had written this article a long time ago. Having these guidelines in place will allow me to check off whether or not my current designs are meeting the criteria. That should be easy enough to recognize. If they don’t meet the criteria I’ll be able to tell and hopefully it will allow me to come up with design tweaks that turn my designs into awesome games.

What’s your design philosophy? I’d love to hear how yours differs from mine. Feel free to share in the comments. Thanks for reading!

Design Me: Manhunt

It’s Friday and I haven’t exercised my brain lately. So today I am doing a Design Me challenge.

Design Me challenges are all about exercising your brain. Like soccer players need to practice when not playing games, so I believe designers should practice their design skills. A Design Me challenge is a great way to exercise your designer mind. So let’s exercise our minds using this combination of theme, mechanics, and victory condition from Boardgamizer:

FBI tile placement with a dexterity aspect! Piece of cake!

If you have never checked out Boardgamizer, go do so right now! You just might be inspired for your next awesome game design.

MANHUNT

Manhunt is a tile (card) placement dexterity game for 2 to who knows how many players. Let’s say 8. So 2-8 players. Each player is given an objective card at the beginning of the game. On each card are two goals. The first player to complete both goals will win this fast-paced fun and interactive game!

Components

This game has very few components. They are:

- 8 Objective Tiles

- 46 City Tiles of varying terrain

- Manhunt tokens

- Objective tokens

- Rulebook

How To Play

Deal each player one Objective tile. This represents that player’s victory condition. Shuffle the City deck and place it face down near the edge of the table. Flip one tile face up and place it in the center of the table. Then flip two more tiles and place them face up next to the deck.

Deal each player one Objective tile. This represents that player’s victory condition. Shuffle the City deck and place it face down near the edge of the table. Flip one tile face up and place it in the center of the table. Then flip two more tiles and place them face up next to the deck.

On your turn you will either choose one of the two face up tiles OR you will draw a tile off the top of the deck. Then you will flip, drop, toss, or whatever you need to do to get the tile onto the table. However, you simply cannot place the card on the table.

No matter where the tile lands it becomes part of the city.

Of course you will want to try to do certain things. Let’s look at the tiles and then discuss some strategy:

Some of the objectives require you to earn Manhunt tokens. To earn a Manhunt token you you to get your tile to cover up a cross-hairs icon. For each icon that you cover you will earn 1 Manhunt token.

Some of the objectives require grouping colors together. So if you can get a group of four brown city sections together then you might meet your objective.

Some objectives could be to get roads together. If you can get three road sections to line up you might meet your objective.

When you complete an objective you should take an Objective token and place it onto your objective tile to indicate that the objective has been met.

So using roads, city sections, and cross-hair symbols you can have a slew of different objectives to meet. The first player who can meet their objectives from their tile will be the winner.

Design Thoughts?

I have successfully exercised my mind and created a tile placement dexterity game that I think could be a fun 10-15 minute filler. I have not played Jason Tagmire’s Maximum Throwdown but I imagine this is similar to that. Sorry, Jason, if this is a rip-off of that. Or I suppose this is similar to FlowerFall. If you think a game like this could be fun, then I suggest you check out Maximum Throwdown or FlowerFall.

Thanks for reading and don’t forget to exercise you designer mind!