Category Archives: Board Games

Game Design Process: Concept

Last week I wrote about prototyping a board game and I shared my prototyping techniques for Scoville. This week I am sharing my concept process. How do I come up with a game design? Do I choose a theme and then add mechanics? Or do I choose a mechanic and then slap on a theme? Do I purposefully try to integrate an appropriate theme for the mechanics? These are the sorts of questions I’m answering today in a “self-interview” format.

Q: Where do you get your inspiration?

A: Everywhere awesomeness can be found. I can be easily inspired by just about anything. Make a game about boll weevils? Sure! Make a game about nuclear radioactive decay? Why Not! My main rule of thumb for game design, whether it’s the concept phase, prototyping, or potentially pitching a game is this:

Make sure it’s fun and relate-able!

If what you are designing is something that is fun, then the theme can be just about anything. I usually get inspired by the things that I waste spend my time on. If I’m enjoying the NCAA basketball tournament I’ll probably start thinking of making a card game where you represent a team in a region of the bracket and via set collection and hand management you have to play the right cards to get your team through the Final Four and eventually to win the championship. If I’m working out in the gym I might be inspired to design a game where you are a person who is trying to lose the most weight. You’d have to compete against the other players to burn the most calories or increase your bench press weight the most. The bottom line, though, is that it must be something fun. Players may love a set collection/hand management game, but if the theme is something boring that no one can relate to, then maybe you should come up with something else.

Q: Regarding a game designer’s Chicken vs. Egg Debate: Mechanic or Theme first?

My inspiration is typically theme based, so I usually start there. I’m not a huge fan of abstract games, either. So that probably guides me toward choosing a theme first.

When you choose a theme first it allows you to sort of steer your game in a direction that fits cohesively. Once you have a theme you can pick and choose the mechanics that you think will work best. Imagine you have chosen the NCAA tournament theme. It would be important to understand how the tournament works. You have 64 teams playing games over several weekends. Each game eliminates one team. Eventually you get to a Final Four. So once you understand how the tournament works you can then start to add mechanics. One way to do this would be to have players each represent one region of the tournament. Your objective would be to get your best team into the Final Four. Other players can play the spoiler role and try to cause upsets in your region. To do all this you could use a blind card mechanic with a drafting round before players apply cards. All players could draft a card and then cards could be played onto each game. The overall idea here is that when choosing a theme first you can then go and apply mechanics that you think fit the theme AND make the game fun.

On the other hand when you choose a mechanic first you are almost automatically starting with a more abstract game. A theme could be slapped on that probably fits the mechanic. Or a different theme. Or another different theme. The reason I typically don’t start with a mechanic is because the theme part of a game is typically what makes a game fun and relate-able. That’s just how I roll!

Q: What about boring themes? People seem to like them too!

Valid point, self. So there are a lot of games that have very boring (my opinion) themes that people still really like. Farming, for example. How can a game about farming be fun? The game Agricola is the third highest rated game on BoardGameGeek.com. So clearly the theme isn’t the whole picture in whether a game is fun or not. In fact, many Euro style games involve “trading” or “resource management,” which can be very boring topics. The key is this:

When the theme is boring, make sure the mechanics are innovative and unique (and fun!) (Or have awesome artwork!)

Sometimes people buy games because of the theme. Sometimes they buy games because of the mechanics. As long as the game is fun it can have a super dry and boring theme and people will potentially enjoy it.

Q: You keep mentioning “Fun.” How do you make sure a game is fun?

When I first got into designing games I searched for articles about making games fun. I found some interesting things that I wanted to list here. Some of them are less about fun and more about making a game “good.” But it’s my philosophy that if a game isn’t good, it won’t be fun. So making a game “good” is a prerequisite for making a game “fun.” Here are my rules of thumb for the conceptual phase of the game design process:

- Interaction is Critical! (Otherwise I’d be designing solo video games!)

- Avoid Downtime.

- Provide many options on each turn – you don’t want players to only have one option on their turn. If they can only do one thing then the cease playing a game and become robots.

- Provide multiple paths toward victory. Even if there is only one victory condition, make sure that there are numerous ways to get there.

- Avoid a runaway winner.

Let’s quickly run through why each of these is important for making a game good and fun:

Interaction: If there is nothing you can do to affect the other players, then you’re playing a solo game against other solo gamers. Not fun. If there is no interaction on a verbal level then it doesn’t matter that you’re sitting around a table with friends. You may as well make your game into an app that people can play when they’re sitting on the toilet. Provide a way for players to interact in the game.

Downtime: No one likes sitting around for a long time while other players are taking their turns. Try to design your game so that people are constantly paying attention. Make sure they’re invested in what the other players are doing. It’s no fun to be sitting around waiting.

Options: Without options a game of strategy or tactics or even luck becomes a simple matter of doing whatever it is that the game is forcing you to do on your turn. That’s no fun at all! Designers: give your players options! Don’t turn us into robots.

Paths to Victory: It’s important for players to be able to play your game in different ways. This can be as simple as having destination tickets like in Ticket to Ride. Or it can be complicated like choosing the best way to fill in your estate in The Castles of Burgundy. Just make sure that you’re giving the players different ways to reach a winning condition.

Runaway Winner: I just as easily could have said to avoid player elimination. With a game where a player can get so far ahead that no one can catch up it is effectively player elimination anyway. A good and fun game design will include a way for players to catch up to a leader. This can be done several ways, including hindering the leader or benefiting a last place player. Think of the NCAA thing again. Which games are more enjoyable to watch, blowouts? or close games where a team was down big and they came back and hit a buzzer beater at the end?

Of course there are other things that can determine whether or not a game is any fun. Those above are just the main five things that I always keep in mind when designing a game. Another one that I did not mention because it is difficult to get right in a game is having an ever increasing amount of tension in a game. That is one of the things that Agricola does really well. This can be done by having limited resources or a first-come-first-serve option. Agricola has both!

Q: You’ve got a theme, now what?

So you’re going with Boll Weevils, huh? Could be worse!

You’ve chosen an interesting theme that could be fun and is relate-able. Where do you go next? I like to do a little research about whichever topic I’m thinking about designing into a game. When doing the research I try to figure out things about the topic that would work well for game mechanics.

In the Boll Weevil example I just learned that boll weevils, though not native to the United States, migrated here in the 19th century and by the 1920s had devastated much of the cotton industry. So perhaps while the boll weevil theme itself may not be very fun or interesting, as a designer I could go several different routes. I could make the game be a cooperative game about controlling the infestation. I could make it so that players represent individual boll weevils trying to infest the largest amount of territory. I could even make the game about farmers trying to grow the best cotton while other players can launch infestations of boll weevils on their opponents. So I could definitely produce a game about Boll Weevils. Question is, would anyone care?

The point is that once you choose a theme, do a little research and figure out what you really want the objective of the game to be.

Q: How do you add mechanics?

Now that you’ve gotten to the point of understanding what your objective is in your game it’s time to start turning it into a real game. The key is understanding the theme. You don’t want to add things to your game that don’t really fit the theme. I recently ran across this with the game Archipelago. There are mechanics in that game that just don’t seem to fit the theme of exploring an archipelago and dealing with indigenous persons. One example is that if the rebels are advancing you can get them to stop by selling fruit. But you aren’t selling fruit to the rebels. You simply have to sell fruit. It just didn’t make much sense to me.

So when I think about adding mechanics to the theme I figure out how the theme really works. It’s like the boll weevil example above. Since boll weevils spread and infest I would probably add a mechanic where a swarm of boll weevils is taking over precious territory.

I also like to keep in mind the 5 points I made above about making a game good. If a mechanic adds too much downtime, for example, I might not go with that mechanic. Or if a mechanic has no player interaction I’d probably leave it out. It is important as a game designer to be cognizant of how the mechanics in your game not only allow for players to reach the game’s objectives, but also to make the game good and fun!

Conclusions:

Game designers face an interesting challenge. The whole idea of creating a game is almost a game in and of itself. Designers strive to make games that are fun, induce emotions from the players, create an atmosphere of engagement between players, and be innovative all at the same time. Finding a theme, applying mechanics, and balancing the game are all things that go into making a great game. If there’s a game out there that you really enjoy, find the designer on Twitter and thank them! A lot went into that game!

Prototyping Techniques Applied to Scoville

While at Protospiel I heard a lot of kind words for the quality of my prototype of Scoville. So today I am sharing my prototyping process with you. I hope that it can help you make a quality prototype that you are confident about.

While at Protospiel I heard a lot of kind words for the quality of my prototype of Scoville. So today I am sharing my prototyping process with you. I hope that it can help you make a quality prototype that you are confident about.

When I was first getting into board game design I was a little overwhelmed by what it took to make a prototype. I watched a few prototyping videos on BoardGameGeek.com. Those only made me shy away from the whole process. It can be intimidating. But today you can learn that it isn’t perhaps as daunting as you might think.

Overview of my Process

First things first: you need a game concept. Assuming you’ve got a great idea in mind it’s time to start prototyping. Early on in my board game career I was designing a heavy Euro game. I waited to make a prototype until I had worked through all the details of the game. That was a mistake. It is my recommendation to make prototype components of your game as early as possible. For example: If you have an auction in your game, test it independently from the other mechanics. Test each mechanic individually and test them early on. There is no point to design an entire game only to find out that the individual parts don’t work.

First things first: you need a game concept. Assuming you’ve got a great idea in mind it’s time to start prototyping. Early on in my board game career I was designing a heavy Euro game. I waited to make a prototype until I had worked through all the details of the game. That was a mistake. It is my recommendation to make prototype components of your game as early as possible. For example: If you have an auction in your game, test it independently from the other mechanics. Test each mechanic individually and test them early on. There is no point to design an entire game only to find out that the individual parts don’t work.

Once the individual elements seem to work then you can try to put them all together to make a full game out of them. Here is a rule of thumb I try to follow:

Never add complications unless they are absolutely necessary.

This is a difficult thing to do. It is always easier to add another rule or add another component. But if you want to make a good game, focus on the innovative mechanic rather than all the little rules about the rest of the game. Keep it simple.

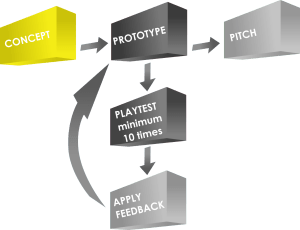

So I start with a concept. I usually write about 10 pages of notes and sketches about that concept. Then I’ll go ahead and start prototyping (this is what I’m covering today). Once I have a prototype ready then I’ll play test it at least 10 times. This will give me a solid amount of feedback. Only after testing 10 times will I apply any changes. Here’s another rule of thumb:

Don’t try to change things in the game on the fly, and don’t change more than one thing at a time.

Following this rule is critical, especially the part about changing more than one thing at a time. If you change more than one thing it can be difficult to know which of the things you changed made the game better (or worse). Change one thing at a time and test it profusely. So I apply feedback and adjust things after 10 play tests. Once the game has gone through the PROTOTYPE – PLAY TEST – APPLY FEEDBACK phase several times to the point where there are only very subtle changes then I get to the point where I am confident about contacting publishers about it. There is no point in pitching a game unless you’ve gotten it to the point where you are proud of your product and confident to show it off.

Getting Started: What do I need?

When making a prototype I usually begin with a spreadsheet. A spreadsheet allows you to create custom tiles or cards very easily. You can print them out yourself and turn them into quality prototype components. Here’s a list of everything I use(d) to create a copy of Scoville:

- Spreadsheet software

- Graphic Design Software (I prefer Inkscape, but The Gimp is also very useful)

- Paper (Plain paper for first prototypes, Glossy photo paper for pitch-able versions)

- Thick card stock – As thick as you prefer, though the thicker it is the more difficult it is to cut.

- Components: cubes/meeples/coins

- Circle Punch

- Paper Cutter (I have this one)

- Bingo chips

- Glue Stick

- Scissors

- Gerber Baby Food Containers – if you don’t have kids find some friends who do and beg them to save these for you!

Here is a picture of all the components that go into the game:

That’s everything (except a box) I need to make a copy of Scoville. Let’s walk through the prototyping (physical creation) process.

Make it Rain! Or Something Like That

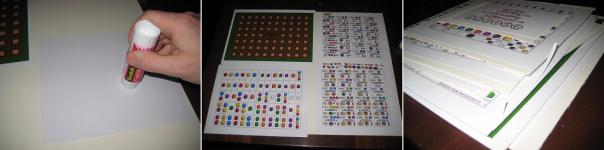

Assuming you’ve taken your concept and created artwork that suits you, it’s time to actually make something real for testing. What that means to me is that it’s time to print stuff out! Scoville has 13 pages of printing required for a full copy. The next step is to adhere those pages to the thick card stock. I like to buy the stuff that is as thick as standard board game chit board. This gives me the feeling like I am playing a real game when I test it.

So I use the glue stick and cover the back of the paper and then stick it to the card stock. Once I’ve got them all glued down I can start to cut them to size. Since the large card stock boards I buy are too big for my paper cutter I run a scissors through them to separate the difference components before using the paper cutter.

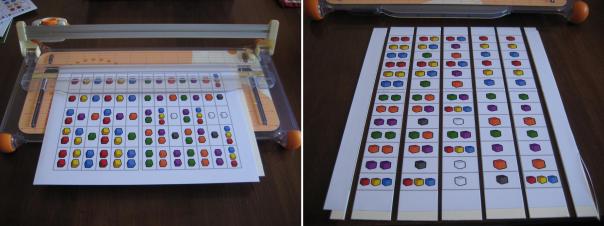

Then I use the paper cutter to trim the fat and make them nice and clean. Shown here as an example is the first cuts done to the auction tiles:

I then go ahead and cut each tile out individually and end up with a pile of nice thick quality components:

I continue this process for all of the components in the game.

Making Player Shields

Another part that seemed a little overwhelming to me was the production of player shields. But I found a nice, easy way to make them. If you don’t want pictures on them then just cut some paper and fold it. If you want pictures or logos then follow this procedure:

-

Print the logos.

- Cut the logos to a rectangular size.

- Glue the logo centered on a sheet of thin card stock.

- Angle cut each edge so that it will lean when completed.

- Fold gently.

For Scoville I made the artwork on the shields include the player color. Making your own player shields rather than using shields from games you own can really spice up your prototype.

Making Money

One of the more tedious things in this process is making my own coins. I don’t have to make it as hard on myself as I do, but I prefer a really professional looking prototype.

It would be much easier to simply write a money value on the plastic bingo chips with a marker. This would make them more difficult to read and they wouldn’t look as nice.

So my process for making coins is this:

- Create the artwork.

- Insert the coin images into a document file.

- Print the document.

- Punch the coins out of the paper.

- Adhere them to the bingo chips.

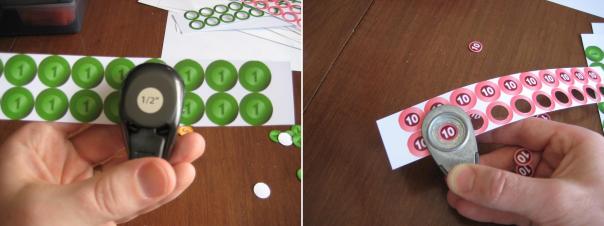

Here is a tip for punching, if you use a circle punch like mine:

If you hold the punch like it seems it should be held then you have to rely on the little plastic bump guides on the side of it. Just flip the punch over and you can visually align the punch with the coin. This makes it so much easier!

Once you’ve got them all punched you can simply glue them to the bingo chips. I recommend watching something on TV that is really attention grabbing, so that it draws your attention from the tedium of gluing little circles to bingo chips.

If you don’t like the idea of gluing circles to bingo chips then go ahead and use the same thick card stock that you’ve been using. Just be aware that the circle punch may not punch through the thick card stock. That’s why I went with the bingo chips.

The Final Product

Once you’ve got all the components glued-punched-cut-etc. then it’s time to put it all together. Here is a before and after picture showing the reduction in volume for Scoville:

To continue with the theme of a quality, pitch-able prototype I like to use a nice container to hold everything. You can buy these at Target.com or you can find different colors in the store. They are only $5. I should also note that these fit into a Medium Flat Rate Priority box from the United States Postal Service. So it is pretty easy to mail one off to a publisher!

Now you’ve got your container so throw in the components, a couple copies of the rules, a business card, and you’re ready to pitch your game! Note, you do not need to have a high quality prototype to pitch a game. I am just a firm believer in making a good first impression. Here’s what Scoville looks like in it’s full prototype form:

This is the third copy of Scoville in existence! May the other two copies in the wild prosper and flourish!

How Much Is It Gonna Cost Me?

I mentioned earlier that you can make an high quality prototype that is also inexpensive. Here is a rundown of the costs for a full copy of Scoville:

- 13 sheets of glossy photo paper: $3

- Printer Ink (I buy cheap Non-OEM ink off Amazon): ~$2

- Glue Stick: $3.30

- 4-Pack of Thick Card Stock: $13

- Bingo Chips: $0.50

- Meeples ($0.14 each): $0.84 – I live near The Game Crafter so I can pick them up and avoid paying shipping costs

- Plastic Cubes (250): $7 – I bought a tub of 1000 cubes for $25 (shipping included) from EAI

So the total for a high quality prototype for Scoville costs me under $30. So maybe you wouldn’t characterize that as inexpensive. But when $30 can allow you to create a pitch-able high quality prototype that might catch a publisher’s eye, I don’t think $30 is too bad.

What techniques do you use? I wanted to point out that I did not write about making cards. Most people, when making prototype cards will purchase penny sleeves, insert their custom made cards, and make them thicker by dropping in a M:TG card. I don’t use cards in Scoville, so I didn’t include that.

I hope that you enjoyed this article. It has been a fun process for me to figure out some of the best ways to make a prototype. If you have any ways to make the process more efficient, please leave a comment so others can see!

The Great Heartland Hauling Company

When I get home today I am hoping that my Kickstarter copy of The Great Heartland Hauling Company will be waiting in my mailbox. During GenCon 2012 I was able to sit down and learn this game from the designer, Jason Kotarski. Jason is a great guy that made an awesome game. The Great Heartland Hauling Company was the first game I backed on Kickstarter. The game uses a “pick up and deliver” mechanic in a very nice and simple package. This game is accessible to gamers and non-gamers alike. And the publishing company, Dice Hate Me Games, recently posted a video for how to play the game. I am sharing that video with you:

How to play The Great Heartland Hauling Company, by Dice Hate Me Games

I really hope the game is there, stealthily waiting for me. Filling up my mailbox. Sitting next to the junk mail that goes straight to the trash. This would be no trash. There is no garbage can in the future for The Great Heartland Hauling Co. This will go straight to the table. And then afterward would find a nice cozy spot on the board game shelves, where it would soon make friends with all the other games in my possession.

UPDATE: For shame… my copy did not arrive today.